BuzzFeed News reviewed 62 incidents of video footage contradicting an officer's statement in a police report or testimony. From traffic stops to fatal force, these cases reveal how cops are incentivized to lie — and why they get away with it.

Officer Nicholas M. Buckley described the arrest in exceptional detail, the single-spaced lines covering two full pages in his report.

He had worked for the San Francisco Police Department for three years, and in recent months he had patrolled the Tenderloin district, a neighborhood of dive bars and homeless shelters wedged between City Hall and the city’s booming commercial center — a neighborhood, Buckley wrote, where “violent, felonious crimes are frequently committed.”

As he and his partner drove past the intersection of Eddy and Taylor streets shortly after 11 p.m. on December 1, 2015, they saw about a dozen men huddled on the sidewalk beside a chain-link fence. The cops suspected the men were gambling. As the officers pulled up to the curb, the men began to disperse.

Buckley homed in on the guy in the long brown coat, Brandon Simpson. While the other men nonchalantly headed north up Taylor Street, Simpson went in the opposite direction and “quickly walked away from the group upon detecting police presence,” Buckley wrote.

He noted what he considered Simpson’s suspicious body language: hands near his waistband beneath his coat. It was “consistent with a person trying to conceal a weapon,” he would later say in court.

Buckley ordered Simpson to stop and show his hands, and when he did not, Buckley “grabbed him by the shoulders.” Simpson resisted and struggled to escape, the officer said. A battle broke out as more officers joined the effort to subdue Simpson, punching and kicking him until they were able to “gain control” and snap on handcuffs, Buckley said. Afterward, officers picked up a white object that had apparently fallen out of Simpson’s waistband or coat. It was a sock with a gun inside of it. Simpson was booked on charges of illegal firearm possession and faced 10 years in federal prison.

On April 13, 2016, officer Buckley repeated his story in a written court declaration, the same story he’d tell a month later on the witness stand during Simpson’s pretrial hearing.

When Buckley had finished testifying, the defense attorney stepped up. She had footage of the arrest, from a surveillance camera on a building across the street.

In full color and crisp definition, it showed what really happened that night.

The police car pulls up. The huddled men stroll away together. A man in a long brown coat near the back of the group — Simpson — walks with them. His arms are at his sides, clearly visible. He holds a water bottle in one hand. Seemingly picking this man at random, Buckley cuts him off on the sidewalk. The man tries to step around the officer. Buckley places a hand on his chest. The man takes a step back. Buckley grabs his arms, pinning his hands to his back. A second police car pulls up. Three officers rush to Buckley and knock the man to the ground. His body disappears beneath the scrum. With the man pinned against the fence, the officers let loose punches and kicks.

Judge Charles Breyer, a long-faced man with combed-down gray hair who often wears a bow tie beneath his robe, was incensed.

“The video was unequivocal in rebutting everything the police officer testified to — at least to all the pertinent details,” he said, before he dismissed the case.

For much of modern American history, police officers were considered, by most judges and jurors, to be the most reliable narrators in a courtroom — professional and neutral arbiters of facts. The increasing prevalence of camera footage eroded that bedrock of the justice system, wiping out powers long held by law enforcement. Within the last half decade, a new reality has set in for cops, lawyers, and judges: Videos have replaced police reports and testimony as the most credible version of events, proving time and again, with increasing frequency, that police officers lie.

BuzzFeed News reviewed 62 examples since 2008, including 40 since 2014, of video footage contradicting a cop’s statement in a police report or testimony. Nine of these videos captured high-profile abuses that led to protests, dominated Twitter timelines, and drew coverage from more than a few national news outlets. The other 53 incidents came and went without much attention beyond that from local residents and reporters. In almost every case, the officers lied for the same reason Buckley did: to retroactively justify their actions.

There are no comprehensive statistical studies of police lying — for somewhat obvious reasons: It’s impossible to know how often officers get away with lying. In one quantitative effort published in the University of Chicago Law Review in 1992, Myron Orfield, who is now a law professor at the University of Minnesota, surveyed dozens of prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges in Chicago. Fifty-two percent of them responded that prosecutors “know or have reason to know” that an officer fabricated evidence “at least half of the time.” Nearly 90% of prosecutors responded that they were aware of police perjury in cases “at least some of the time.”

San Francisco officer Buckley lied in his police report, in his court declaration, and in his testimony. He lied about his reason for approaching Simpson, and the video showed that he violated Simpson’s constitutional rights by stopping him without reasonable suspicion and then detaining him without probable cause.

“Why do they do it? The main reason they do it, historically and now, is they can get away with it.”So it didn’t matter whether or not Simpson had a gun. The stop was illegal, Judge Breyer ruled in his dismissal of the case, and so the evidence it produced was legally useless. Prosecutors dropped the charges and informed Buckley’s bosses.

Eight months later, Buckley remains on the force. The department would not say whether he has been disciplined but told BuzzFeed News that “this is still an active and open Internal Affairs investigation.” Federal prosecutors have not charged him with perjury and would not comment on the case.

Lying is “something that has been endemic in the history of the American police system for the last three or four generations,” said Peter Keane, a former San Francisco police commissioner who now teaches law at Golden Gate University. “And why do they do it? The main reason they do it, historically and now, is they can get away with it.”

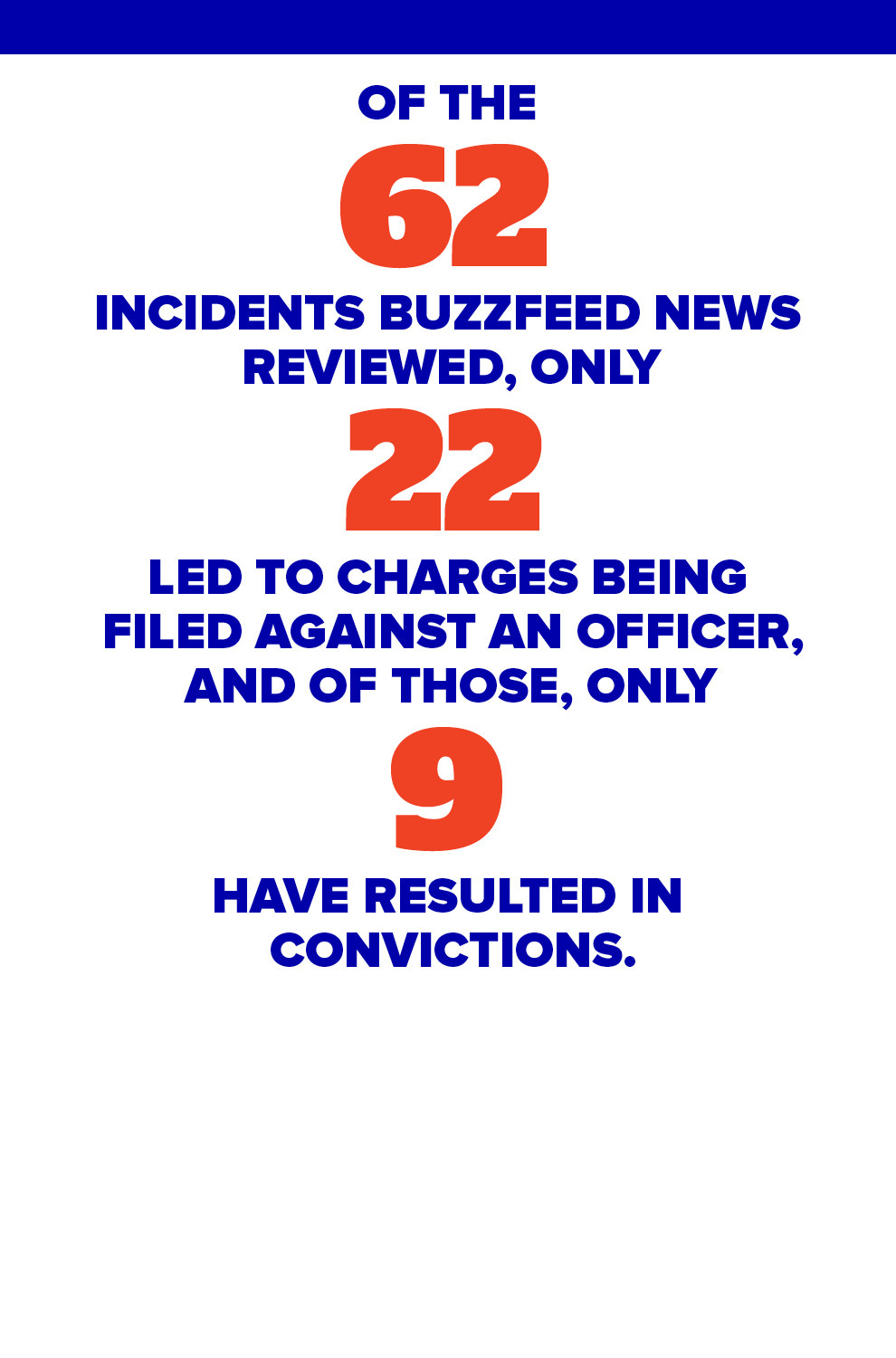

Of the 62 incidents BuzzFeed News reviewed, only 22 led to charges being filed against an officer, and of those, only nine have resulted in convictions.

Click or Tap to play any video. Sources: The Post and Courier (Slager); WRDB (Corder); New York Daily News (NYPD); Chicago Police Department (Sierra); San Francisco Public Defender (Henry Hotel); Toxic Cops / YouTube (Krawetz); The Free Thought Project / YouTube (Marion, FL); Polidic / YouTube (Horses); WFAA 8 (Baker); Reading Eagle (Santiago-DeJesus); St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Stockley); Felipe Hemming / Youtube (Evansville Police).

Cameras prove cops lie, and there are more cameras out in the world today than ever before. While its depth is unknown, the scope of police lying is wide. Officers lie in high-profile cases and little-known cases, and lie by fabrication, omission, and exaggeration.

Police officers lie when they or one of their colleagues kill. Officer Michael Slager, of North Charleston, South Carolina, claimed he fatally shot Walter Scott because he feared for his life after Scott grabbed his Taser and pointed it at him, but video showed Slager shooting him in the back from 17 feet away, then dropping his Taser by Scott’s body. After Chicago officer Jason Van Dyke shot Laquan McDonald 16 times, five cops claimed that McDonald lunged at Van Dyke with a knife, but the video showed the teenager walking away. They lie when they beat up people who were not resisting arrest. Officers Sean Courter and Orlando Trinidad of Bloomfield, New Jersey, claimed that Marcus Jeter hit one officer and tried to grab the other’s gun, but video showed the officers pulling him out of his car and immediately assaulting him. Five Marion, Florida, cops claimed Derrick Price resisted arrest, but video showed that he was on the ground surrendering with his hands up when the officers began punching and kicking him. They lie when they think no cameras are watching, like Reading, Pennsylvania, officer Jesus Santiago-DeJesus did when he smashed Marcelina Cintron-Garcia’s cell phone and arrested her on a false charge of assault after she filmed him during a traffic stop. They lie when they should know for certain that cameras are watching, like officers in Seabrook, New Hampshire, in Skokie, Illinois, and in Sweetwater, Florida, did when they slammed and injured suspects getting booked into their police stations, then falsely claimed the suspects had acted aggressively.

They lie when witnesses are around. New York City officer Paula Medrano failed to mention in her accident report that pedestrian Felix Coss had the right of way when the police van she was driving fatally struck him in broad daylight. They lie in groups, like the six cops in San Francisco, four in Chicago, and three in Kissimmee, Florida, who lied about having probable cause to arrest a suspect for drug possession. They lie when no other cops are on the scene. Bullitt County, Kentucky, sheriff’s deputy Matthew Corder arrested Deric Baize for disorderly conduct and resisting arrest, claiming that he “caused alarm to neighbors,” but video showed that Corder entered Baize’s house and tased him only after Baize had cursed at him for blocking his driveway. “Next time you tell a police officer to fuck off,” Corder said, “you might want to think about it.” They lie in big cities. Houston officer William Wright accused Julian Carmona of pointing a gun at him at a gas station, but video showed that Carmona had merely picked up his gun when it fell out of his truck before quickly placing it back inside. Baltimore officer Vincent Cosom claimed to have punched Kollin Truss at a bus stop in self-defense, but video showed that Truss was walking away, with his arms by his side, when Cosom attacked. Los Angeles officers Michael Ayala and Leonardo Ortiz claimed that Brian Beaird, who was unarmed, was reaching for his waistband when they fatally shot him, but video showed that Beaird’s arms were raised at his sides. They lie in small towns. Neenah, Wisconsin, cops reported that they shouted a warning before opening fire and killing an innocent man during a hostage standoff, but video of the incident “does not give any indication that there was a verbal command given,” the town’s police chief acknowledged. Lincoln, Rhode Island, officer Edward Krawetz claimed that he kicked Donna Levesque in the face “to defend” himself from serious injury, but video showed that she had lightly kicked his leg while sitting handcuffed on the curb. Evansville, Indiana, cops said that officer Nick Henderson hit Mark Healy because he was resisting arrest, but video showed that Henderson struck him because his hand got stabbed by a needle in Healy's pocket. They lie by omission, like the officers in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and San Antonio, Texas, did when they failed to note in their statements that the suspects they fatally shot had their hands up in surrender. They lie by exaggerating or downplaying, like Bay Area Rapid Transit officer Nolan Pianta did after he violently slammed Megan Sheehan, then wrote in his report that he “guided her to the ground.” They lie by outright fabrication, like King County Sheriff’s Office Sgt. Lou Caballero did when he falsely accused a bus driver of cursing at him. Or like Jackson, Georgia, officer Sherry Hall did when she accidentally shot herself, then reported that a black man had done it. Police officers lie about traffic stops. Kentucky state trooper Phillip Burnett arrested motorist Freddie Gregory on the false claim that he was “menacing” the officer after he ticketed him for not wearing a seatbelt. Dallas Sgt. Stephen Baker falsely claimed Marcial Salazar ran a red light. Some of them keep up the lie even in the face of the video evidence. Confronted with his own dashboard camera footage in court, Baker still refused to back down. "I don't make too many mistakes," he said, even as the defense attorney repeatedly played a clip showing that Salazar had a green. When internal affairs investigators later asked Baker to explain his obviously false statements in court, Baker told them that he hadn’t been able to tell whether the light was red because he didn’t have his reading glasses with him. And those are just since 2008 and just what’s been caught on camera.

A cop’s word is often the difference between a person’s freedom and imprisonment. In many cases, an officer and a defendant tell diametrically opposed versions of the same incident — a “swearing contest,” lawyers call it — and a judge or jury is left to decide whom to believe: the professional law enforcement agent who has testified in dozens of trials or the undereducated, underemployed, probably black or Latino guy from an “area known for narcotics trafficking” accused of breaking the law? The scale is even more unbalanced when the word of the defendant is lined up against the words of not one but two, three, four, five professional law enforcement agents. “The words of the police officers would always prevail over the words of poor black and brown folks,” said Craig Futterman, a professor at the University of Chicago law school. Police aren’t supposed to take sides in court, but of course they do. It serves their purpose to defend the legitimacy of the arrest and the evidence they gathered and handed to prosecutors. They do the investigative legwork for prosecutors and meet with them to discuss case strategy. It’s no surprise, then, that cops often emerge as the prosecution’s best witnesses, their experience on the stand contrasting with a defendant’s understandable nervousness, their veneer of neutrality hiding their personal belief in a defendant’s guilt. “In criminal cases officers are given a higher degree of credibility,” said Tom Grover, a former Albuquerque Police Department sergeant who now works as a defense lawyer. “They are seen as having no stakes in the matter, of just doing their duty.” Some jurors see right through this veneer. An officer’s usual aura of credibility doesn’t hold up as well in cities with large black and Latino communities filled with residents who have long distrusted police, said Futterman. Derwyn Bunton, chief public defender in New Orleans, can recount many occasions when, during jury selection, the judge would ask the roomful of prospects, “Who would you trust more: your neighbor or a police officer?” “Very often people chuckle out loud,” he said. “And this was before video evidence became as big as it is today.” Yet even healthy skepticism of police officers has failed to overcome the decades of tradition and legal precedent working in their favor. That much was clear after 28-year-old Terrance Bostick was arrested on drug trafficking charges in 1985. Two Broward County Sheriff's Department officers had found cocaine in Bostick’s bag while he sat on a bus in Florida. According to the officers’ account, it was all so easy: They stepped onto the bus, told Bostick they were cops, asked permission to search his bag and informed him of his right to refuse, and Bostick consented. Bostick, however, claimed that he never agreed to the search. No other witnesses testified.

Prosecutors, defense attorneys, and police officers from around the country said they’d seen a surge in how often criminal cases hinge on video evidence.

In his ruling on whether the search was constitutional, Judge Russell Seay called the officers’ story “highly improbable.” “Why would a cocaine smuggler consent to a search that could send him to prison for decades?” he wondered. But the judge declared that he had no choice but to grant the police the benefit of the doubt. “When you've got sworn testimony from two police officers and they're testifying, sometimes you don't have much other than that and you have to go along with the sworn testimony, but it does really stretch the imagination,” he wrote. Bostick was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. But the presumption of police honesty has become an antiquated convention. “And,” former police commissioner Keane said, “it’s only starting to change for one reason: video.” Just as the new DNA evidence of the last two decades proved with scientific certainty that cops sometimes coerce suspects into false confessions, video footage in recent years exposed that cops sometimes open fire on people who pose no threat. This new criminal justice landscape was born from the intersection of two historical trends. First came the technological advancement that suddenly multiplied the number of cameras out in the world. As cameras became smaller and cheaper, more business owners could install them on their buildings, more city governments could stick them on light poles, more police departments could clip them to their uniforms, and more people could easily access them on their mobile phones. New York City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, which handles accusations of police misconduct, reported that it found more false police statements in 2014 than in the previous four years combined, largely because of an increase in video footage. Prosecutors, defense attorneys, and police officers from around the country told BuzzFeed News that they’d seen a surge within the last few years in how often criminal cases hinge on video evidence. According to the Washington Post’s database of police shootings, the number of them caught on video increased from 142 in 2015 to 231 in 2016.

“We’re seeing an explosion of video in public places coming to us from many different sources,” said San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón, who previously served as the city’s police chief. “We’re seeing things today that we would not have seen 10 years ago, and I think that’s very healthy. If you were looking at a graph of a curve, you’d see gradual increase, and then all of a sudden it’s like a pogo stick within the last two or three years, post-Ferguson.” Colliding with this new technological reality was a new civil rights movement sparked by two deaths that were not caught on camera. The details of what happened in the moments before George Zimmerman killed Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, in 2012 and officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 have been — and probably will always be — heavily debated. In both cases, the shooters were not convicted of any crime, fueling further protests declaring that “black lives matter.” “You’re seeing people pull out their video cameras much more often when they see a police interaction in the street,” Gascón said. “It’s a new era for us.” Every few months since the Ferguson uprising, new videos emerge showing police officers killing black men, producing a string of national news headlines — Walter Scott in North Charleston, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Laquan McDonald in Chicago, John Crawford in Beavercreek, Sam DuBose in Cincinnati, Mario Woods in San Francisco, Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, and others. In many of these cases, the videos directly contradicted the police version of events. From 2005 to 2014, an average of six officers a year were charged with murder or manslaughter, according to a study by Bowling Green University professor Philip Stinson. In 2015, prosecutors filed those charges against 18 officers; more than half of them had been filmed in the act. Though these well-known cases are among the most egregious examples of police misconduct in recent history, they represent only a portion of police deception. The list of known lies grows longer with each fresh clip.

“The ubiquity of video today has made it impossible for broader society to deny the reality and prevalence of police abuse in black and brown communities."

“This is a paradigm shift,” said Futterman. “The ubiquity of video today has made it impossible for broader society to deny the reality and prevalence of police abuse in black and brown communities. It provides objective evidence of what folks in those communities have already known for years. And now that the jack is out of the box, there’s no putting it back. It’s triggered an ongoing conversation that isn’t going away.” Video is our most undeniable, and our most easily digestible, form of evidence. It does not always answer all our questions. Recordings from three cameras were not enough to reveal whether Keith Lamont Scott held a gun when Charlotte police killed him. But a video tends to reveal enough to challenge, if not disprove, the official police account. Its value, then, is in its power to break through the delusion of American comfort, the willful or accidental ignorance many of us maintain because, as James Baldwin explained in 1964, “life is beautiful, and in order to keep it beautiful you’re going to stay just the way you are and you’re not going to test your theory against all the possibilities outside. America is something like that. The failure on our part to accept the reality of pain, of anguish, of ambiguity, of death has turned us into a very peculiar and sometimes very monstrous people.” But with each video, thrust onto screens across the country, this reality exposes itself just a bit more; the water around the iceberg drains a few feet and it turns out the thing looks even bigger than many of us thought, and who knows how much more is down below, unseen?

There are two overarching, sometimes overlapping, reasons officers lie. The first is to keep themselves out of trouble, to avoid criminal charges or losing their job after a shooting or a beatdown or a questionable arrest. This is the one we most often hear about, in the aftermath of high-profile police abuse, when Sandra Bland is found dead in jail or Eric Garner suffocates on the pavement. It’s messed up, unethical, immoral, unacceptable, but also a simple act of self-preservation by a person who must have recognized that they’d done wrong.

The other reason cops lie is to lock up a suspect who they know — or think they know — is guilty even though they have insufficient evidence to make a legal arrest. “When an officer is stretching the truth, it’s often driven by the belief that they’re meeting with a person who has committed a crime and in order to protect the community and get that arrest and conviction, you push the line,” said Gascón, the district attorney and former police chief. “But that’s just as much of a violation of the rules.” Kissimmee Police Department officer Tiffany Hall seemed to believe that Jonathan Elliott was guilty. She and her colleagues had a tip that people were trafficking drugs at the Tropicana Motel, an orange and white inn flanked by palm trees and dried grass along a stretch of highway dotted with cheap lodging. Hall and several other officers staked out the building on the evening of November 24, 2015.

"When an officer is stretching the truth, it’s often driven by the belief that they’re meeting with a person who has committed a crime."

As the motel’s surveillance footage would later show, two men knocked on the door of room 208, and another man — Elliott — let them inside and closed the door. After a few minutes, the two men left. Hall and two other officers got a room key from a motel employee and entered 208, where they found a bag containing around 30 grams of weed. They arrested Elliott for marijuana possession. Problem was, the officers had violated Elliott’s Fourth Amendment rights. They did not have a warrant to enter his room. And so, in her police report, Hall described a scenario that met all constitutional requirements, a tale she would repeat in testimony: She claimed that she watched the two visitors hand Elliott a bag “containing a green leafy substance” as they stood at the open doorway of the room. She went on to describe a drug bust that went smoothly, almost laughably so: In Hall’s version, the officers knocked on the door, Elliott opened it, Hall spotted the bag of weed on a nearby table, and Elliott “stated ‘here’ and handed me the plastic bag.” Elliott, who had a burglary conviction on his record, asserted that the police version was false, but he didn’t expect people to believe him. "Usually, a story like that coming from someone like me who has a past of doing things, it's not usually believable," he told the Orlando Sentinel. But he informed his court-appointed attorney, Catherine Conlon, that he had noticed a surveillance camera outside his room. Osceola County prosecutors did not know the footage existed, and when Conlon brought it into court, they dropped the charges against Elliott and instead filed criminal charges against Hall, for perjury and falsifying records, and the two other officers, for official misconduct. The Kissimmee Police Department suspended the officers without pay. This drive to catch the bad guy by any means necessary was not developed in a vacuum. Cops feel institutional pressure to make arrests. In many, if not most, police departments, arrests are a primary metric with which to measure an officer’s ability and work ethic. Michael Baysmore, who was a patrolman with the Baltimore Police Department for two years before joining Coppin State University's force, recalled that the path to promotion within the BPD was through arrests — a high volume of them or a string of high-quality ones, like gun busts or big drug seizures. “The people who really paid the most attention to arrests were the ones trying to get into specialized units, the ones trying to make a name for themselves, trying to stand out,” Baysmore said. “Whenever your evaluations would come up, if you got a negative review it was probably because you were one of the people on your shift with the least number of arrests.” Temptation to falsify hovers over a cop like a devil on the shoulder. Letting a probably guilty suspect get away makes an investigation feel “almost like a waste,” Baysmore said. He recalled such an instance from September, when he responded to a call of theft at a building on Coppin State’s campus. Somebody had stolen two cell phones from an office on an otherwise vacant floor of the building. The surveillance tape showed a young man get off the elevator on that floor around the time the phones went missing, then leave the building a few minutes later. Shortly after that, another camera, too distant to capture clothing details or facial features, showed a blurry figure walking toward a bus stop nearby. Inside a trash can next to the bus stop, Baysmore found a cell phone case and IDs belonging to the owners of the phones. “So I knew it was him, but at the same time I really couldn’t prove it,” he said. There were no witnesses and no other relevant surveillance footage. There was just a young man who was near the scene of the crime when it occurred and, shortly after, may have been near where the evidence was found. “If I tried to write up the probable cause statement based on that, the state’s attorney won’t take the case,” Baysmore said. But if, in his report, he had invented some reason, some pretense, to search the young man, perhaps he would have found the cell phones and gotten the arrest. Instead, Baysmore let it go. “A couple of officers I work with, they were saying, ‘You shoulda just locked him up!’”

This is an age-old police dilemma, to get the bad guy at any cost or to play by the rules no matter the cost. “A professional police officer,” retired NYPD detective Marq Claxton said, “realizes that you can work well within the parameters of the law and still be effective. That is the job.” In practice, however, there have long been officers under the impression that the job allows for shortcuts. Richard Uviller, a prosecutor in New York City for 14 years who spent eight months embedded with the NYPD for his 1988 book, Tempered Zeal, found that the “most common form of police perjury” involved officers inventing probable cause after an arrest. “The instrumental adjustment,” he called it. “A slight alteration in the facts to accommodate an unwieldy constitutional constraint and obtain a just result.”

The officers believed these practices were necessary to compensate for a criminal justice system that they saw as too lenient. Several cops, both active and retired, told BuzzFeed News that in recent years the courts have only gotten more forgiving, the expectations on police have only gotten higher, and the job is harder now than it has been in decades. “You add in the additional oversight that everybody’s calling for, this decrease in confidence and trust from the community, this policing model based on enforcement, and you’ve got pressure on all ends,” said Claxton, who policed in the 1980s and ’90s. “You’re gonna have people who make false statements under the guise of they need to do this in order to protect the system because, the way they see it, the Constitution is so restrictive it won’t let us catch the bad guys.” Another NYPD detective, who worked from the early ’70s to the late ’90s, said, “Who would wanna become a cop today? I have young guys in my neighborhood asking me if they should become a cop. I told them to become a fireman.” The detective, who requested anonymity to speak openly about his career, recounted how easy it was to make arrests back in his day. “I made seven gun arrests in eight hours once,” he said. “We would drive down the streets and anybody that looked at us a certain way, we would chase them, throw them up against the wall, and the gun would fall to the ground. That maybe wouldn’t stand up today. But we knew the guy was a bad guy and we just did what we had to do. I don’t know if I could be a cop today.”

“Today, as soon as you stop somebody, you have 20 people standing around there with phones taping you."

Within the last decade, as crime rates reached new lows and the general public was not as worried about public safety, lawmakers rolled back many of the tough-on-crime policies of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. The videos of fatal police shootings brought fresh, heightened scrutiny to law enforcement and spurred protesters to call for changes in departmental practices. “Today, as soon as you stop somebody, you have 20 people standing around there with phones taping you,” said retired NYPD detective Jay Salpeter. “Which I think is a good thing for the cop, too. A cop has the ability to take your life.” Baysmore, the Baltimore cop, said that he now always assumes a camera, somewhere, is watching him while he’s on the job. It makes him nervous sometimes, that a clip gets taken out of context, that the blurring whirl of a tense situation gets frozen into its most damnable elements, that his memory slips up at the wrong time, that a small inconsistency in his report gets blown up and next thing he knows his photo is on the evening news and protesters are calling him a liar. “When you’re out there dealing with stuff, you’re just reacting,” he said. “You just have a split second to react and do something, so you might not remember everything they said or you said or every movement. In the back of your mind you try and have a photographic memory, but at the same time you’re trying to apprehend a suspect.” Early in his career, his reports contained every detail he could remember. Now, he plays it safe, the second-guessers always lingering in the back of his mind, alongside the worry that a seemingly inconsequential instance of misremembering — the color of the car, the type of fence the suspect threw the drugs over, the alley he cut through during the chase — could irreversibly poison the arrest, undermining the credibility of all his words. “If there’s something I’m not totally clear about, I just won’t put it in there,” he said. “I keep it shorter. I won’t add words I don’t have to.” Those in the police world insist that the Baysmores far outnumber the Buckleys and the Halls. “Ninety-nine percent of officers are really good,” said Dan Klein, a retired Albuquerque police sergeant. It’s an ongoing frustration for many officers that the other “1%” are the ones most well-known to the public. “That’s the world we live in,” said Joe Gamaldi, vice president of Houston’s police union. “A situation where an officer gets accused of excessive force, that’s going to be the thing that people hear about.” As officers see it, those outliers, broadcast to the public over and over, cascade into a growing wave of anti-police sentiment; hence, an entire profession judged by the worst among them, the crumbs defining the reputation of an otherwise respectable institution. “Every time there’s a bad incident caught on video, it makes it that much harder to recover,” said John Cornicello, a retired NYPD detective. “In between all that, there are all the good interactions we don’t hear about. The ones we don’t see, of course, are all the times where nothing bad happened.” The consensus police version of this story is that the abuse and the lies and the unjustified killings are the work of “bad apples.” A recent poll by the Pew Research Center, for example, found that two-thirds of officers believe that the police killings of black people in recent years are “isolated incidents” and not “signs of a broader problem.” If this conclusion is not entirely convincing, it might be because of how deeply embedded the misconduct appears, how normalized, how easy it seems to come to the officers performing rogue acts with minds untethered from consequences. It’s a comfort that suggests institutional acceptance. “It’s not just the rotten apples,” said Geoffrey Alpert, a criminology professor at the University of South Carolina. “It’s the rotten culture that allows the rotten barrel that creates the rotten apples.” A rotten culture of policing is perhaps the only way to explain what happened in a case Chicago defense attorney Steve Goldman worked in 2014. During a surveillance operation sparked by a tip from an informant, police officers pulled over his client, Joseph Sperling, and found a duffel bag filled with weed in his car. Goldman obtained the dashcam footage from a police cruiser at the scene. When the officers testified about the arrest during a pretrial hearing, Goldman realized, “Oh my god, they have no idea we have this video.” Five officers took the stand and “started saying the exact same thing like it was scripted.”